Why this topic is important

The concept of scope is one of the most crucial in JavaScript, and in programming in general. Yet, it’s also one of the most common sources of confusion.

What is scope?

In simple, simple terms, scope defines:

The lifetime of a variable

Where it lives

Where it’s accessible from

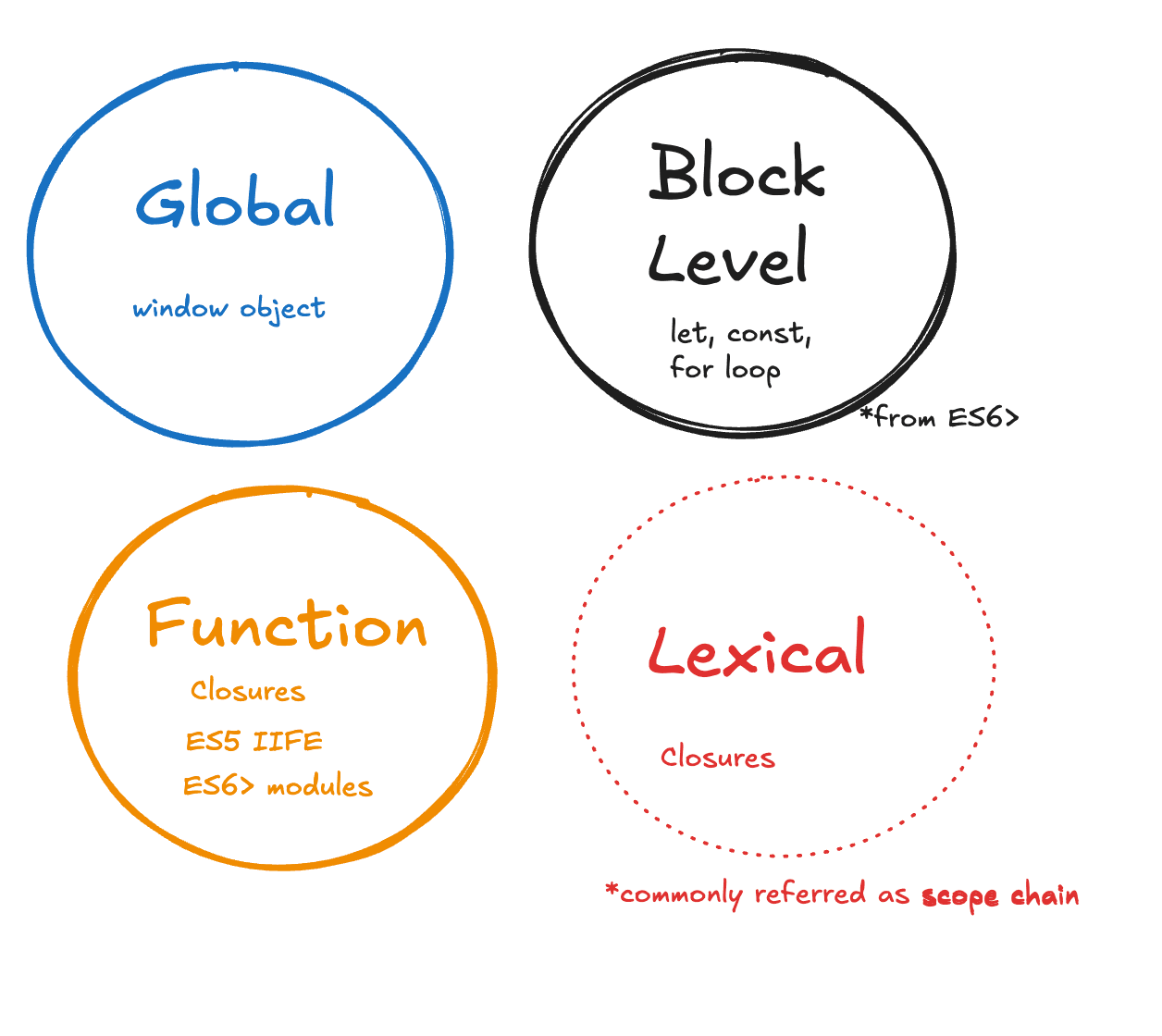

That's really it. And in more simpler terms, they are of three types plus one 'special', let's say:

Let's see them in detail.

1. Global Scope

The global scope refers to the window object (in browsers).

Everything declared here is available throughout the entire JavaScript application.

While convenient, this can easily become problematic in large applications, which is why, over time, new ways to handle variable lifetime were introduced.

Global scope still exists today, but modern JS provides better alternatives.

2. Block Scope

Introduced with ES6, block scope is defined by curly braces .

Variables declared with let and const inside a block exist only within that block.

For example, loops (for, while) and conditionals (if) also create their own block scope.

3. Function Scope

Variables declared within a function are accessible only during that function’s execution.

Before ES6 modules, function scope was heavily used to prevent polluting the global scope, often through IIFEs (Immediately Invoked Function Expressions).

4. The Special one: Lexical Scope

The Lexical Scope, also known as the Scope Chain or Lexical Environment, is not a separate scope that we can directly access from our code as we do with the other types mentioned before. It is an intrinsic part of each scope and not a tangible one, but rather an abstract construct, implemented in different ways, depending on the browser engine.

Conceptually, a Lexical Environment consists of two areas:

Environment Record: that is an object that holds all the local variables, and the value of this

Outer Scope Reference: that is a reference to the lexical enviroment right outside

Every time a block scope, a function, or something in the global scope is declared, it automatically comes with an associated Lexical Scope.

Functions in JavaScript remember the lexical environment in which they were defined, not where they’re called.

This concept forms the foundation of closures, which we’ll explore in this article: JS Fundamentals: Closures, The Fridge That Keeps Data Fresh.

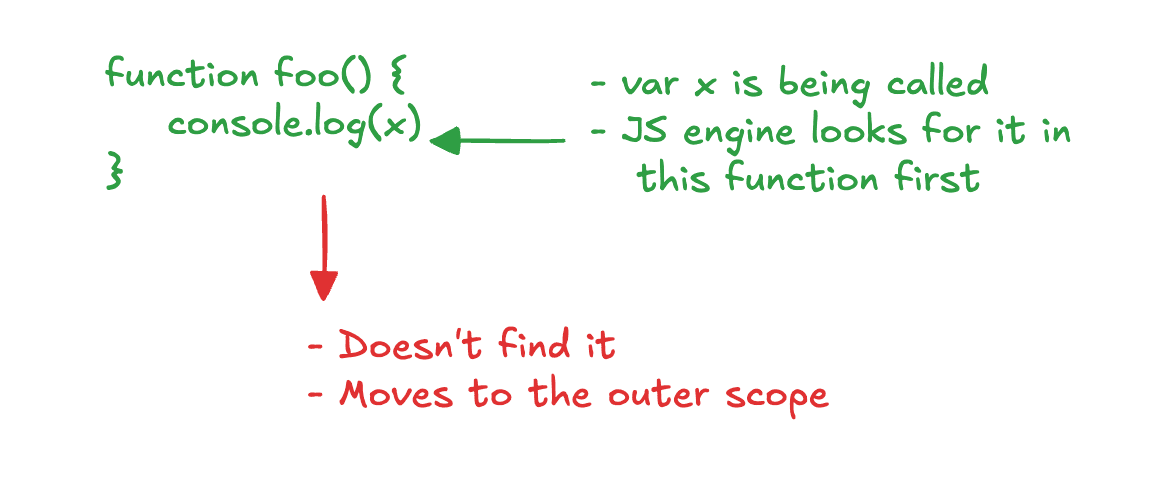

How Does The Scope Chain Work

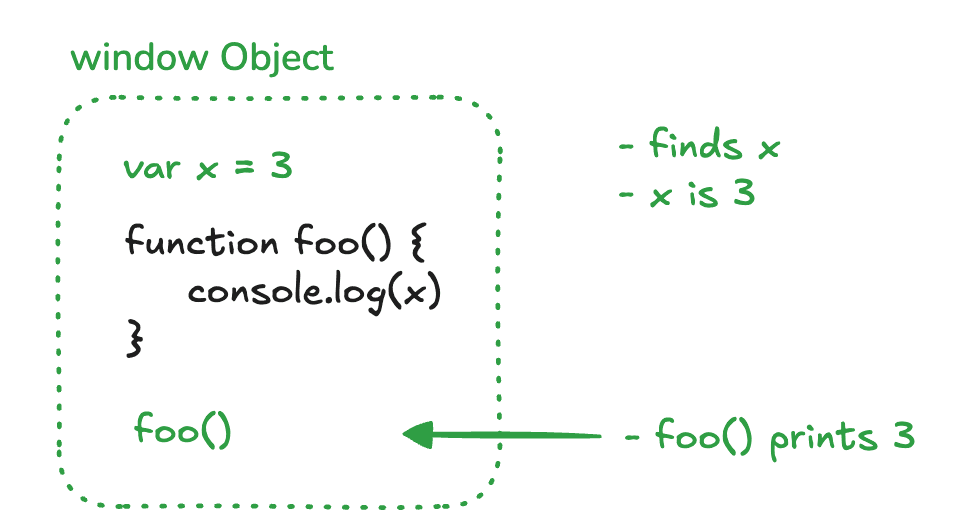

When you use a variable, the JavaScript engine searches for its declaration starting in the current scope.

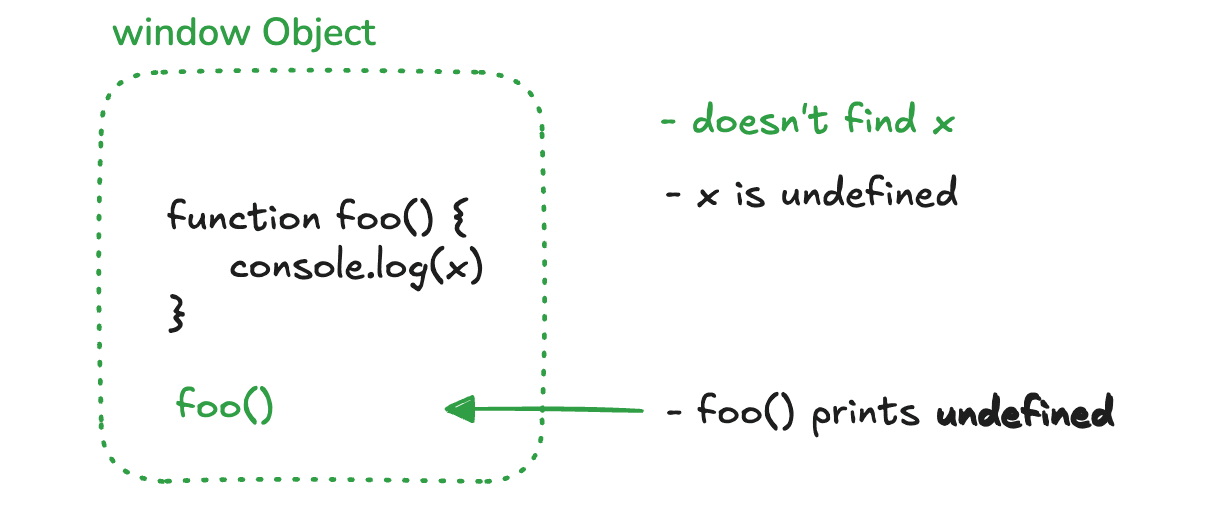

If it doesn’t find it there, it looks in the outer scope, then the next one up, and so on, until it reaches the global scope (the window object in browsers).

If the variable isn’t found even there, JavaScript throws a ReferenceError, or, in some cases with older constructs like var, sets it to undefined.

Hoisting

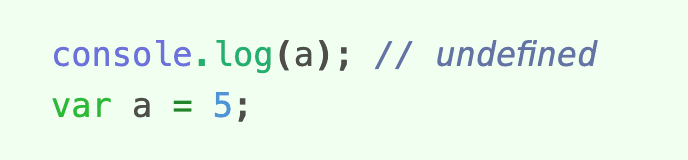

During the compilation phase, the JavaScript engine moves all variable declarations (not initializations) to the top of their scope.

Here, the declaration of a is hoisted, but not its value.

If you try to access a variable before it’s declared with var, you get undefined.

With let or const, things work differently, leading us to the next topic.

The Temporary Dead Zone (TDZ)

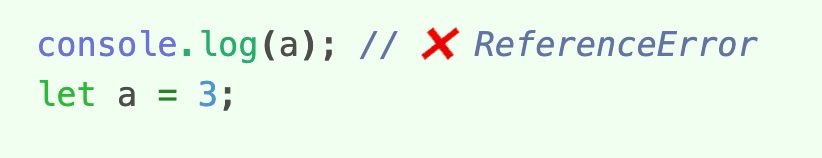

The Temporary Dead Zone (TDZ) is the time between a variable’s declaration and its initialization, the moment the JavaScript engine allocates memory for it but before it assigns a value.

Accessing a variable in this period throws a ReferenceError.

Here’s what happens behind the scenes:

1 - During the compilation phase, the JS engine knows that a exists (it’s hoisted)

2 - But it doesn’t assign it a value yet, it’s in the “dead zone”

3 - Only when the line let a = 3 is executed does the variable leave the TDZ and become accessible

Why the TDZ exists

The TDZ prevents common bugs and unpredictable behavior that were possible with var.

Before ES6, variables declared with var were hoisted and initialized to undefined, even before their declaration line, often leading to confusing results.

This could cause subtle logical errors in large codebases.

let and const fixed that by ensuring variables can’t be accessed before initialization, making the language more predictable and safer.

To summarize:

TDZ starts from the beginning of the scope where the variable is declared

TDZ ends when the declaration line is executed

Accessing a variable in the TDZ results in a ReferenceError, not undefined.

let and const are still hoisted, but without initialization.